Open ChatGPT, ask “What happened with the French election last night?”, and it spits back a crisp, sourced summary. In two sentences it covers who-won, the turnout, and the market reaction.

Five years ago Google would have sent you clicking through five blue links. Today the package and the distribution belong to the model.

That’s strike three for the incumbent news business. Strike one was the open web, which moved distribution from the physical world to digital. Strike two was social media, which took away traffic and ad dollars. Strike three is AI, which threatens to swallow the interface itself.

Below are the distilled results of my conversations with ChatGPT’s o3 model and how I currently think the shake‑out could go—ending with a (plausible?) bull scenario in which parts of the industry actually come out stronger.

1. What the model still can’t do

Ben Thompson’s Aggregator Theory holds that power flows to whoever owns the consumer relationship in a world of zero distribution cost. A perfect chat assistant is a super‑aggregator: it intermediates not just between publishers and readers but between everything and everyone. Yet the assistant, like Google today, fails without quality inputs—that’s where media comes in.

Publishers therefore move from supplying finished pages to supplying verified atoms of information. In economic terms they become complements to the aggregator, not substitutes—and complements can get paid.

Even a hallucination‑free super‑model can’t manage three things:

Original reporting. Someone still has to phone the reluctant source, sit in a courtroom, or fly to Gaza to get the story.

Be a trustworthy brand. "Written by The Economist" carries more weight than something a random user posts on X.

Provide proprietary context. Think FT’s Lex, Bloomberg Terminal data, neighbourhood polling spreadsheets—assets a crawler can’t grab for free.

2. Where will the money come from?

Obviously the big question is how will the publishers get paid. I expect that we’ll end up with an extrapolation of the hybrid model that we’re already seeing, where there’s be a mix of platform licensing, direct-to-creator, and meta associations of smaller publications that get paid by traffic:

Platform licensing:

Large models pay to ingest archives and promise to keep live, branded links in answers. This is already starting to happen. OpenAI has struck deals with the Associated Press, Axel Springer (worth “tens of millions of euros a year”), Le Monde/Prisa, the Financial Times and, most lucratively, News Corp (rumored quarter-billion dollars over five years).

DTC (Direct-to-Creator) & Subscriptions

Substack has proved that consumers will back individual journalists: the platform already processes more than five million paid subscriptions. As AI captures the lion’s share of distribution, expect more journalists to go independent to own their audience.

Established brands like The Economist and the New York Times will continue to monetize mostly on subscriptions for exclusive access to its content. In an attempt to drive more value to their offering, I expect publishers to bake their own fine-tuned models/off the shelve solutions into paid apps or terminals—BloombergGPT already lives inside the Bloomberg Terminal.

Collective-rights “label” for small & local publishers

A hub (call it NewsRights) aggregates the catalogues of local dailies, weeklies, blogs and newsletters too small to negotiate alone. It licenses the pool once and splits fees back to members via transparent view‑/token‑/referral logs, keeping an admin fee for audits and lobbying

The hub meters LLM calls/links to the source articles, pays members pro-rata from the license pool, and keeps a % admin fee for audits and lobbying. This is already starting to happen with the Authors Guild’s proposed collective-licensing body, and the UK’s AI Collective Licence due Q3 2025 all point to this model gaining speed.

3. Bear Case – The sums still don’t clear the payroll

The wave of licensing cheques looks impressive in press releases—News Corp’s “historic, multi-year” deal with OpenAI is the headline example—but even optimistic industry estimates put the payout at roughly a quarter-billion dollars spread over five years. That is barely one quarter of a single year’s newsroom costs at the Wall Street Journal and its siblings, let alone the rest of the group.

Scale those ratios across the broader market and the pattern repeats:

Top-tier brands (NYT, FT, Axel Springer, News Corp) might eventually collect high-single-digit % of revenue from AI licences—but investigative and foreign desks routinely burn 15–20 % of turnover.

Mid-tier nationals and business trades live on thinner margins; 2–4 % in new licence income cannot offset the collapse of open-web display ads and the extra head-count now demanded by trust & safety rules.

Indie and local outlets still sell almost nothing directly to the models. Their collective-rights societies (Raptive in the US, new UK schemes) are months away from first payments and the early projections are in the low-five figures per site.

At the same time the interface is moving further upstream: ChatGPT alone already fields ≈ 1 billion queries every day, about 7 % of Google’s daily search volume.

The resulting pincer squeezes the middle::

Costs stay stubborn: you still need reporters on the ground even if AI massively accelerates editing.

Clicks decline faster than licence rates climb as most searches end-up with zero clicks.

Only the very largest and the very smallest have economic lifeboats—giants via scale and negotiating power, one-person shops via ultra-low overhead.

Everything in between is at risk (like today, but worse).

4. Bull Case – Usage explodes and the pie inflates

A more hopeful trajectory looks like this:

Query inflation. Voice and multimodal agents embed in cars, earbuds, office suites and watches. If total “information-seeking events” explodes by 2030, the pool of high-intent traffic could be larger even if each individual answer sends out fewer clicks. I see this trend in my search queries to LLMs. The majority of searches I do are things I’d never even bother asking Google, they can be long-multi-day conversations where dozens of citations are included, and much more immersive that Google Search. And it will only get better.

Mandatory links & brand surfacing. Every major media‑AI deal (OpenAI, Perplexity, Apple, Anthropic) mandates live, attributed links. As long as that clause survives antitrust and copyright tests, more queries mean more qualified referrals.

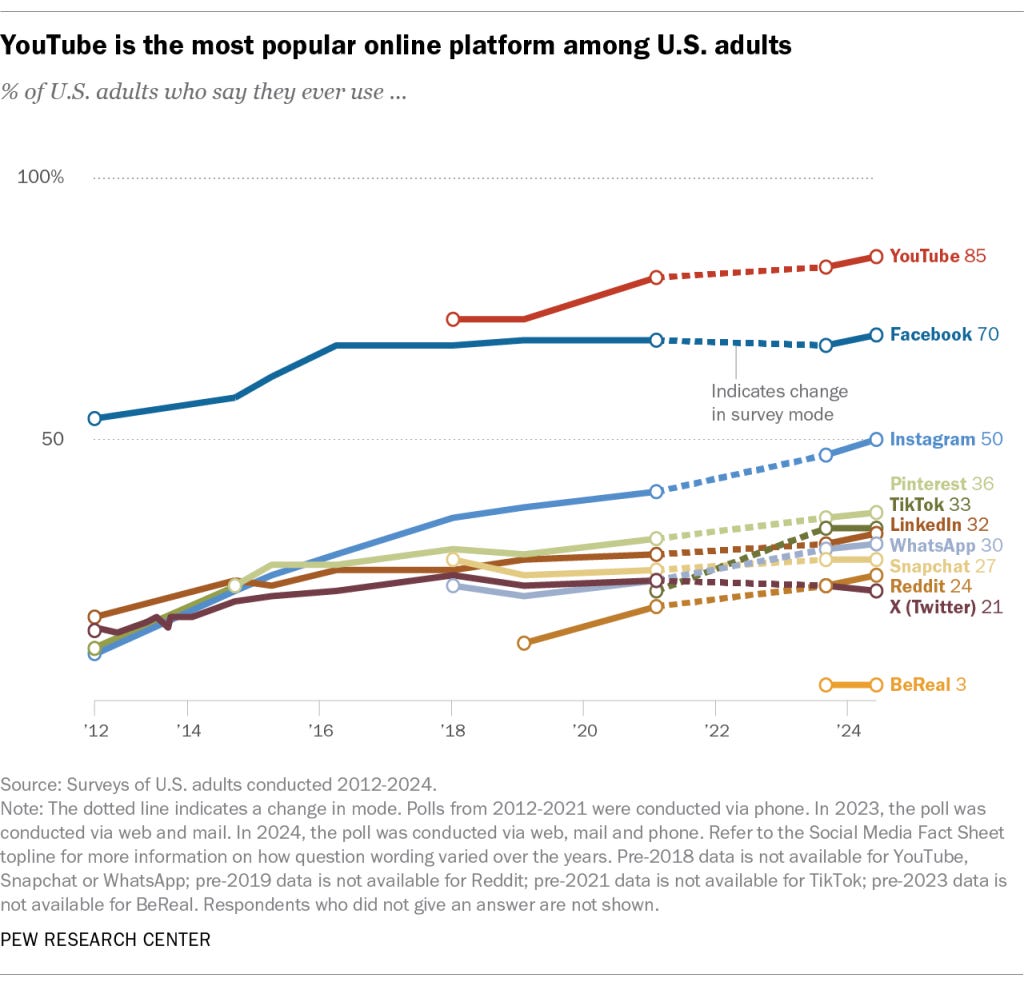

Diversified revenue. Media doubles down on video content. Every media publication becomes a Youtube creator. Viewers want the seeing-is-believing layer that text-only LLM answers can’t replicate. About a third of U.S. adults already get news on YouTube, matching Facebook for the top spot. I only see this growing. Almost all of my media consumption from outlets like Bloomberg or DW are from their Youtube channels, be it via news shorts or longer form documentaries. As production costs fall, the algorithmic feed grows more central; outlets that skip the game (as many did with Facebook or Twitter) will lose relevance fast.

AI-driven productivity. AI-assisted research, translation and video editing makes editing and distribution a story much cheaper, leading to leaner newsrooms who can spend marginally more revenue in the finding and reporting on the stories.

5. A great sorting out

The likely outcome is a barbell effect: a few global, multidisciplinary news brands on one end; hyper-specialist, creator-led outfits on the other; little room in the middle.

If I ran a mid‑sized publication, I’d:

Go all‑in on video. Push daily shorts with bite-sized news, trend‑jacking explainers and turn investigative pieces and interviews into longer documentaries. Produce free video content that’s good enough for people to dabble with your paid offering.

Fix the core digital product. Nobody will visit a site where 30 % of the screen is ads or clickbait—especially when an AI can read, speak or chat back the same information on demand, in any language.

Embrace AI. Deploy AI for research, translation, editing and distribution now—by design, not desperation. Write for the AIs.

It’s a hard job, unpredictable, and I’m not even sure that this are the right recommendations.

But picture the morning after Netscape’s IPO in 1995. Would you have doubled down on classifieds, or started shipping HTML? That’s where publishers are today. Those who move first will write the stories tomorrow’s assistants quote.